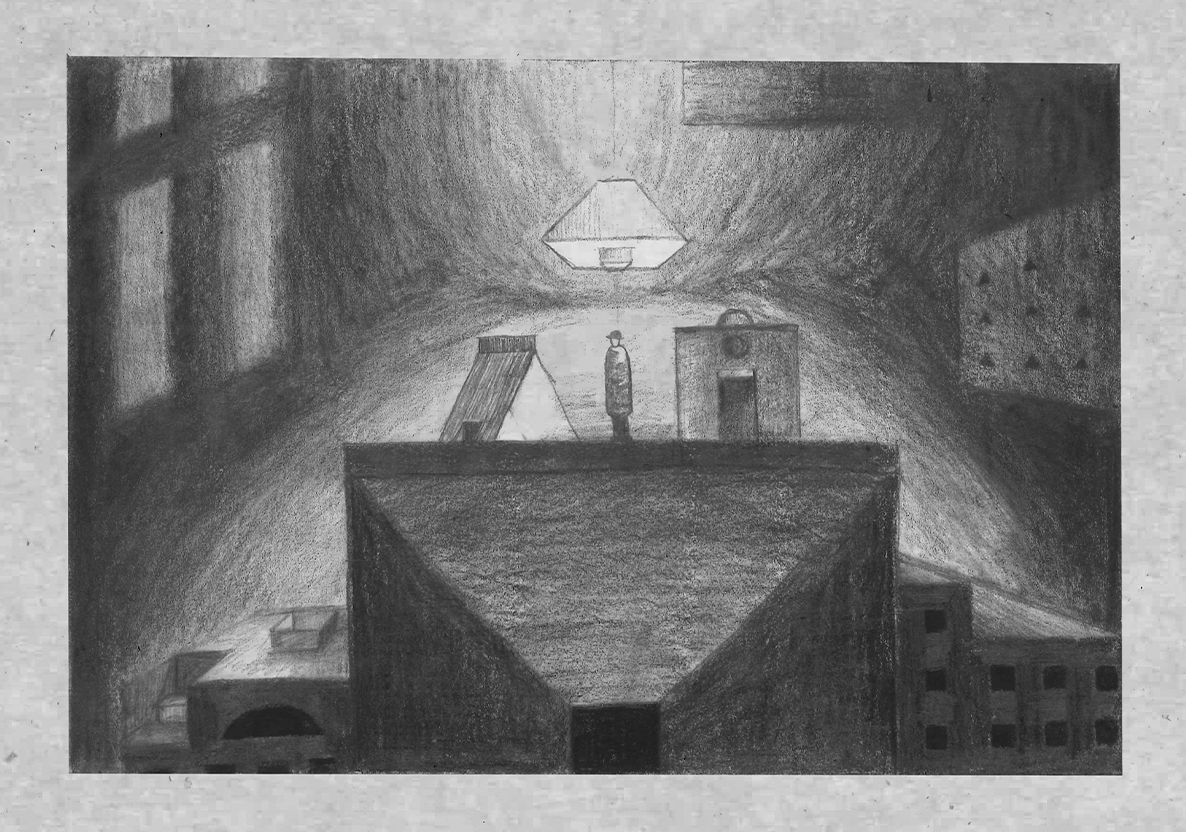

The road ahead is blocked, so,

we'll have to take the bypass lane,

the ancient track, the path less taken.

The one that they-who-came-before-us walked.

The one that leads by rivers, valleys, forests, mountains,

The one that — did it lead to the ocean?

We might have to take a boat.

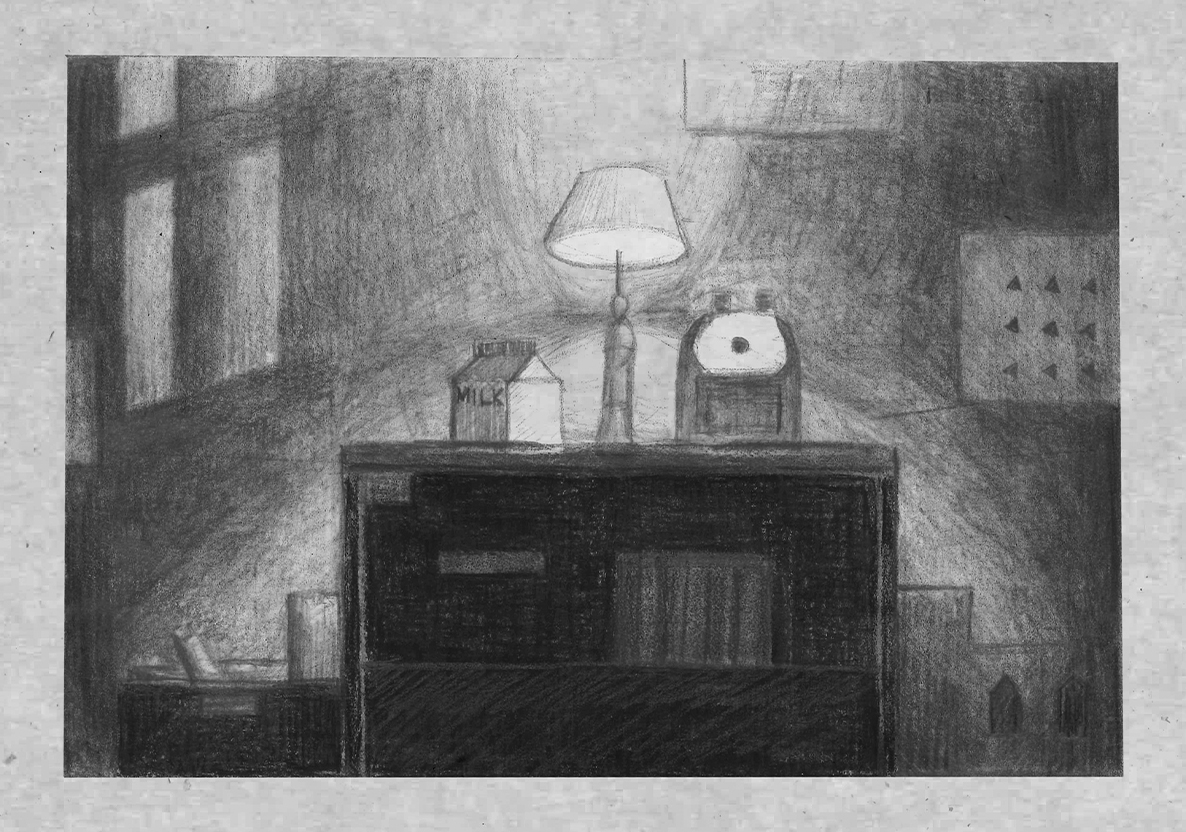

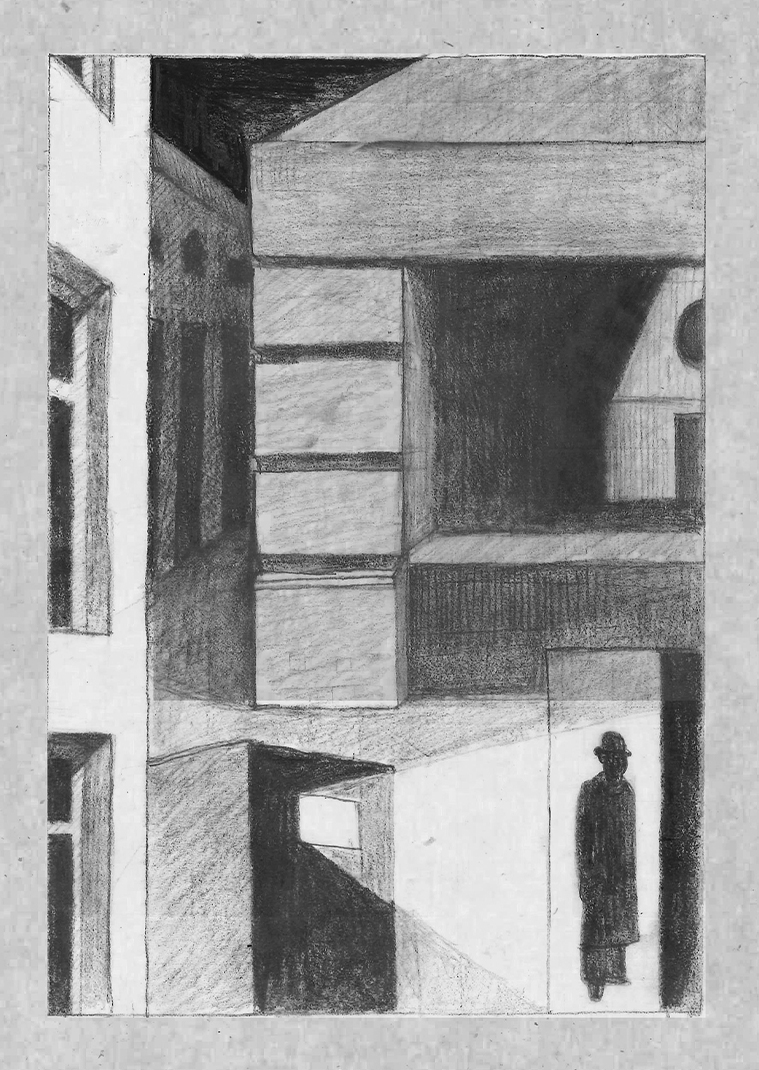

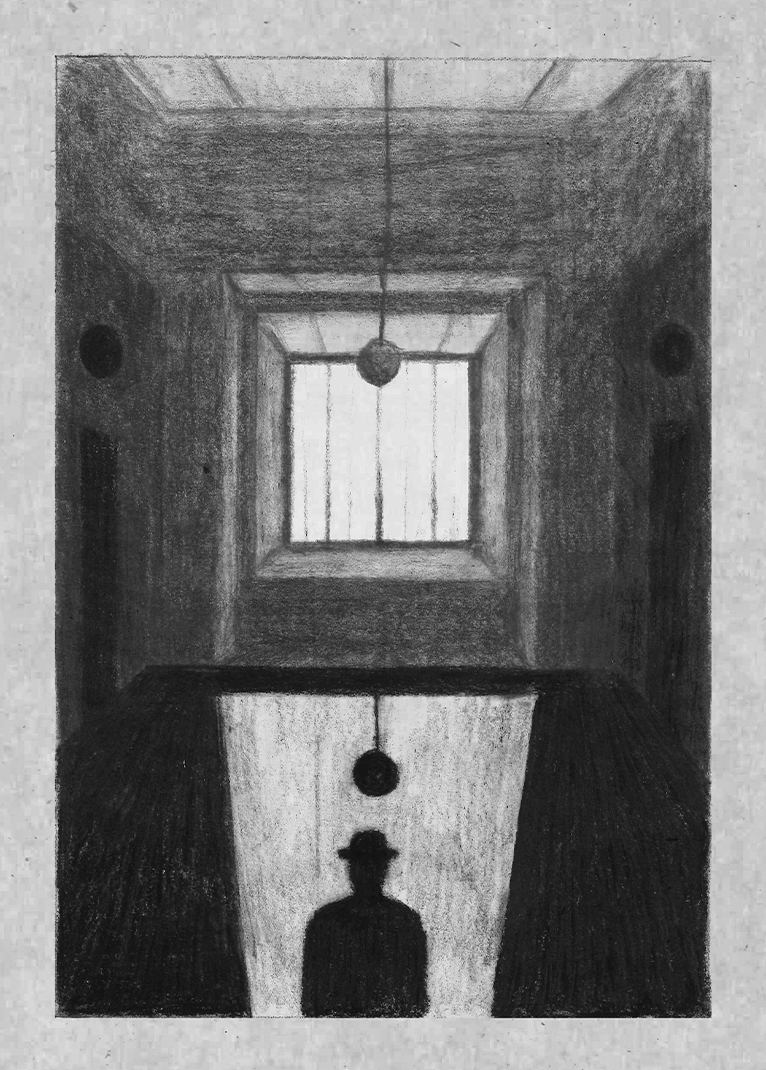

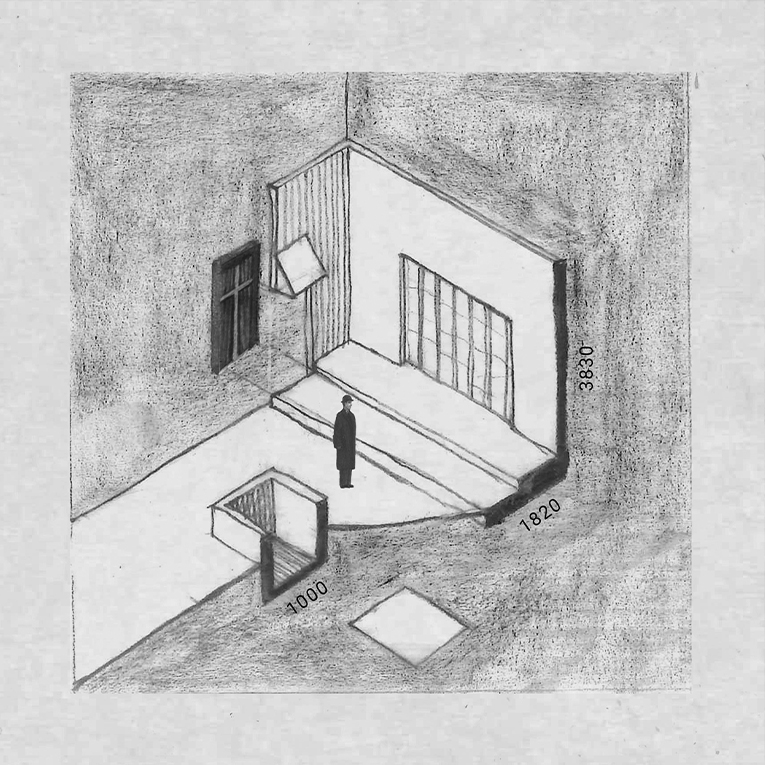

Architecture remains stranger to me.

we'll have to take the bypass lane,

the ancient track, the path less taken.

The one that they-who-came-before-us walked.

The one that leads by rivers, valleys, forests, mountains,

The one that — did it lead to the ocean?

We might have to take a boat.

Architecture remains stranger to me.

identity and discourse

[About the identity of architects]

What is the identity of the architect today? Within practice and discourse, we tend to identify ourselves as generalists. Working within our supposedly heterogeneous field means we are (roughly) in tune with (some) aspects of philosophy, society, history, culture, nature, technology, politics, economy . . . and so on. This identification is often masked by verbose language; weavers of ideas and knowledge from near and far; polymaths; storytellers; spatial constructors and navigators. Yet, for as much as architects swear commitment to world-making, the majority of our work is still rather detached from life.

To the public, we carry neither this grand image nor significance. Instead, architects today are commonly thought of as building specialists, and this may be true. We are expected to be ordered and controlled, otherwise ‘simply’ an aesthetician, accompanied by connotations of a total ‘visionary’ nutjob. People look elsewhere when they want to deal with more pressing issues. This identification is partly stereotyped, and partly formed by our own hands. In academic institutions, students are mostly trained within technical or conceptual boundaries. Critical thinking is encouraged, but ultimately supplementary to the output. Professional practice is hardly any more accountable, seemingly complicit to an unethical system of business and development. It’s not so bad if you just play by the rules.

Why this interest in identity? I myself am unsure. Try, as the Modernist avant-garde might have, to break from the past, but our genealogy we cannot deny. Perhaps we cannot help ourselves — human nature triumphs — questions arise, and we must explore them. We must look back through history and time at stories of why-we-are-who-we-are. Against this we may measure our current value systems within our social universe.

An undercurrent within large international architecture firms: the architect who can, through computational programs, analyse a whole city in a week, and from that data develop projects. I can’t say I know my own friends and family as precisely as this. Even they have their own undiscovered mysteries.

Another undercurrent within architecture in general: the architect who designs and photographs their projects as objects on the outside, and as bespoke, high-class, yet empty showpieces on the inside. The ethics of these projects are post-rationalised; first to the client, then to the public; and that is enough. Even behind beauty there is politics.

Architecture is supposedly interdisciplinary — but only if those disciplines bend themselves to fit into the paradigm of architecture. We position everything in relation to architecture, and not the other way around. Are we growing from what already exists, or are we transplanting?

What is your identity as an architect today? We ourselves may not know much about architecture, but each of us does have our own sensibility and moral code. Where does your work come from? Is your identity not shaped by factors beyond your professional obligations — matters that are more important? What is higher in hierarchy… life perhaps?

Another undercurrent within architecture in general: the architect who designs and photographs their projects as objects on the outside, and as bespoke, high-class, yet empty showpieces on the inside. The ethics of these projects are post-rationalised; first to the client, then to the public; and that is enough. Even behind beauty there is politics.

Architecture is supposedly interdisciplinary — but only if those disciplines bend themselves to fit into the paradigm of architecture. We position everything in relation to architecture, and not the other way around. Are we growing from what already exists, or are we transplanting?

What is your identity as an architect today? We ourselves may not know much about architecture, but each of us does have our own sensibility and moral code. Where does your work come from? Is your identity not shaped by factors beyond your professional obligations — matters that are more important? What is higher in hierarchy… life perhaps?

[About discourse in architecture]

When we can’t make architecture, we must draw, write, speak — any way to record and ensure that ideas can still circulate. This is our mode of discourse, and we pride ourselves in this continual conversation. In fact, discourse seems to be the way out of our own limitations, and the way we might rewrite our relationship with the public. Of course, built architecture has its own language too — through a city plan or a house, you say what you are thinking about life.

What happens when we speak a private language that cannot be understood? In fact, most discourse remains internal within the round table of architecture. Some discourse is inaccessible even to architects themselves. The polemic holds no relevance, and as such finds itself in tension with reality. As meaningful as these conversations are, an inaccessible language will do little to invoke thought, let alone encourage change. We need a translator.

When we can’t make architecture, should we just lay dormant? Critical discourse is important — it is our method of inquiry. But the conversations we often share with other architects are rife with platitudes. We avoid saying what ought to be said. By limiting the range of our debates, the spectrum of acceptable opinions, we keep ourselves . . . passive and indifferent. Hidden are the deeper things we long to express, with the little nothings we naturally say.

[The identity and discourse of bypass]

Nevertheless, as young architects-to-be, we find ourselves swept into this current. bypass is not our manifesto to propose the way out. What we publish is not definitively advocating for a ‘new architecture’. Instead, bypass is a manifestation of our feeling that the currents are shifting.

In recent times, we’ve bore witness to the effects of climate change, the human rights movements, political conflicts, the coronavirus, and other arising matters of the world at large. Upon this increasing awareness of the fluid nature of reality, and of our own constant state of flux, many assumptions, classifications, and definitions are falling apart. How can we live today? What does it mean to be an architect today? What is the work of architecture today? Are these the concerns that we, as young architects, should spend time thinking about? It feels amateurish for me to ask of this.

In recent times, we’ve bore witness to the effects of climate change, the human rights movements, political conflicts, the coronavirus, and other arising matters of the world at large. Upon this increasing awareness of the fluid nature of reality, and of our own constant state of flux, many assumptions, classifications, and definitions are falling apart. How can we live today? What does it mean to be an architect today? What is the work of architecture today? Are these the concerns that we, as young architects, should spend time thinking about? It feels amateurish for me to ask of this.

One shift in the current: the desire of architects, students included, to regain the wisdom architecture once had. To value local and other expressions of knowledge, aside from the language of academia. To perhaps reshape our own identity.

Because architecture is not just ‘buildings’. The worlds that we construct mirror back to us our collective values. The spatial and temporal phenomena of architecture speak of our social norms, political agencies, environmental influences, economic stances, and cultural habits. These contexts have their implications, and we need to hold ourselves accountable.

We will make mistakes. We might be confrontational and take a bite out of something much bigger than we imagined. We might not be here for long. We’re OK with these things. We are receptive and prepared to learn.

bypass is offered as an open collection of ideas that could become a foundation for other ways to approach your own architecture. We view our naivety and openness to ideas as a virtue against what we think is an increasing internalisation of discourse. Sometimes we ask, “what did the text really mean?” and other times we ask, “how does this text produce meaning?”.

Even if ‘radical’ today is doomed to become ‘stereotypical’ tomorrow, we do not wish to stop asking the questions that at least cause us to consider the possibility of change.

Because architecture is not just ‘buildings’. The worlds that we construct mirror back to us our collective values. The spatial and temporal phenomena of architecture speak of our social norms, political agencies, environmental influences, economic stances, and cultural habits. These contexts have their implications, and we need to hold ourselves accountable.

We will make mistakes. We might be confrontational and take a bite out of something much bigger than we imagined. We might not be here for long. We’re OK with these things. We are receptive and prepared to learn.

bypass is offered as an open collection of ideas that could become a foundation for other ways to approach your own architecture. We view our naivety and openness to ideas as a virtue against what we think is an increasing internalisation of discourse. Sometimes we ask, “what did the text really mean?” and other times we ask, “how does this text produce meaning?”.

Even if ‘radical’ today is doomed to become ‘stereotypical’ tomorrow, we do not wish to stop asking the questions that at least cause us to consider the possibility of change.

Ethan Yu-Teng Chung